Overcoming Common Injuries: A Guide for Powerlifters

Written by The Boostcamp Editors

Overcoming Gym Injuries: Powerlifter's Ultimate Guide

Following a training routine is easy when things feel great, but you will inevitably hit a roadblock and even potentially get injured. Injuries are common in any sport, whether that is a strength sport or performance based sport, and powerlifting is no stranger to this. A powerlifting injury can often set you back and even end your career if you don’t have a roadmap to get back to lifting. When it comes to powerlifting injuries, not all of them are created equal. However, the essence of rehab stays the same. You want to build things back up and return to the platform stronger than before. In this article, you will learn how to overcome common injuries in powerlifting.

Note: The information presented in this article is not to be taken as medical advice and is intended for educational purposes only. If you are injured and need support, please seek a health care provider to ensure you obtain proper care for your particular situation.

Table of Contents

What is an injury?

How often do powerlifting injuries happen?

What causes powerlifting injuries to happen?

Roadmap for navigating powerlifting injuries

Programming strategies for the injured powerlifter

Supplementary care for the injured powerlifter

Conclusion - find an entry point

What is a Powerlifting Injury?

Before you learn how to overcome powerlifting injuries you need to understand what exactly a powerlifting injury is. An injury refers to any physiological damage to your living body typically caused by physical stress. They can occur intentionally or unintentionally via a myriad of mechanisms such as blunt force trauma, overuse, overexertion, etc. Now there is some nuance here as ‘damage’ happens all the time in your body. In fact, it’s how your muscles grow bigger and get stronger after every workout. However when this damage exceeds your tissue tolerance or your ability to recover, you can end up with an injury.

In the case of powerlifting, you can think of something being an injury when you are unable to perform the demands of your sport over a long period of time. In this case, only when you are unable to do the big three compound lifts, (squat, bench, or deadlift) over a few training sessions could you be considered injured due to the inability to move or bear weight. There are many times where you may be sore and may even have pain, but this is not considered injured if you can still do the activity or movement with no modifications. Knowing this can help you distinguish whether the sensations you are feeling are par for the course or need to be checked out by a professional.

For example, if you have some back soreness and pain but can still squat, then this is fine and not considered an injury. If you have some back soreness and pain impacting your ability to squat for a few sessions, then you can consider yourself injured. If you haven’t experienced this you likely will at some point, but don’t worry it’s not the end of the world. Injuries are part of the game and knowing how to deal with them is what sets you apart to continue doing this sport for the long run, regardless of your age or fitness level.

How Often do Powerlifting Injuries Happen?

Like any other sport, injuries are quite common in powerlifting especially in sub-elite powerlifters (1). Although they are common, the injury rate is relatively low compared to contact sports (2). Some research used data from multiple powerlifting clubs and calculated the injury rate to be 0.3 injuries per lifter per year. That’s about 1 injury per 1000 hours of training (3). In addition, 43.3% of powerlifters complained of problems during routine workouts. In terms of where injuries happen, the most commonly injured body regions were the shoulder, lower back and the knee (3). Men and women both have similar injury frequencies but locations do differ (1).

Although injuries are present in powerlifting, rarely do they require a complete interruption of training (1)(3). This is great news because it means that with most injuries that you will deal with in powerlifting still allow you to train and make progress. Of course there is a huge variety in the severity of powerlifting injuries and each has their own respective path. But the key here is that there is a way for you to overcome whatever injury you face and keep on lifting. You’re probably thinking how you can accomplish this, but first you have to have an idea of what causes powerlifting injuries to happen in the first place.

What Causes Powerlifting Injuries to Happen?

The thing about injuries is that it’s multifactorial. There are lots of factors to consider as to why you may have been injured, although you can be pretty sure what resulted in your injury in the case of severe trauma. Otherwise, anyone who tells you exactly why and how you got injured is probably just giving you their best guess. The research suggests that there is no specific data that tells us why injuries happen in powerlifting (1)(2)(3)(4)(5). However, there are some relationships and possible risk factors you can think about that are correlated with powerlifting injuries.

Training load

The seemingly biggest factor when it comes to why powerlifters get injured is related to overall training load (1)(2)(5). Sometimes the workload is too much for your tissues to handle, and the overall load exceeds your tissue capacity. This can be over time or a one-off event such as when you attempt way over your one rep max and are not prepared for it. Other times and likely more common is that you may simply be doing too much too soon, which can lead to workout injuries. Think about when you are peaking for a competition, or running a very intense program. You naturally start to ramp up intensity and do more to prepare you for competition. This is when injuries have a higher chance of happening due to the increased training load. It’s not a guarantee, just a matter of probabilities. If you find yourself constantly getting injured, you’ll want to assess your programming and overall training loads.

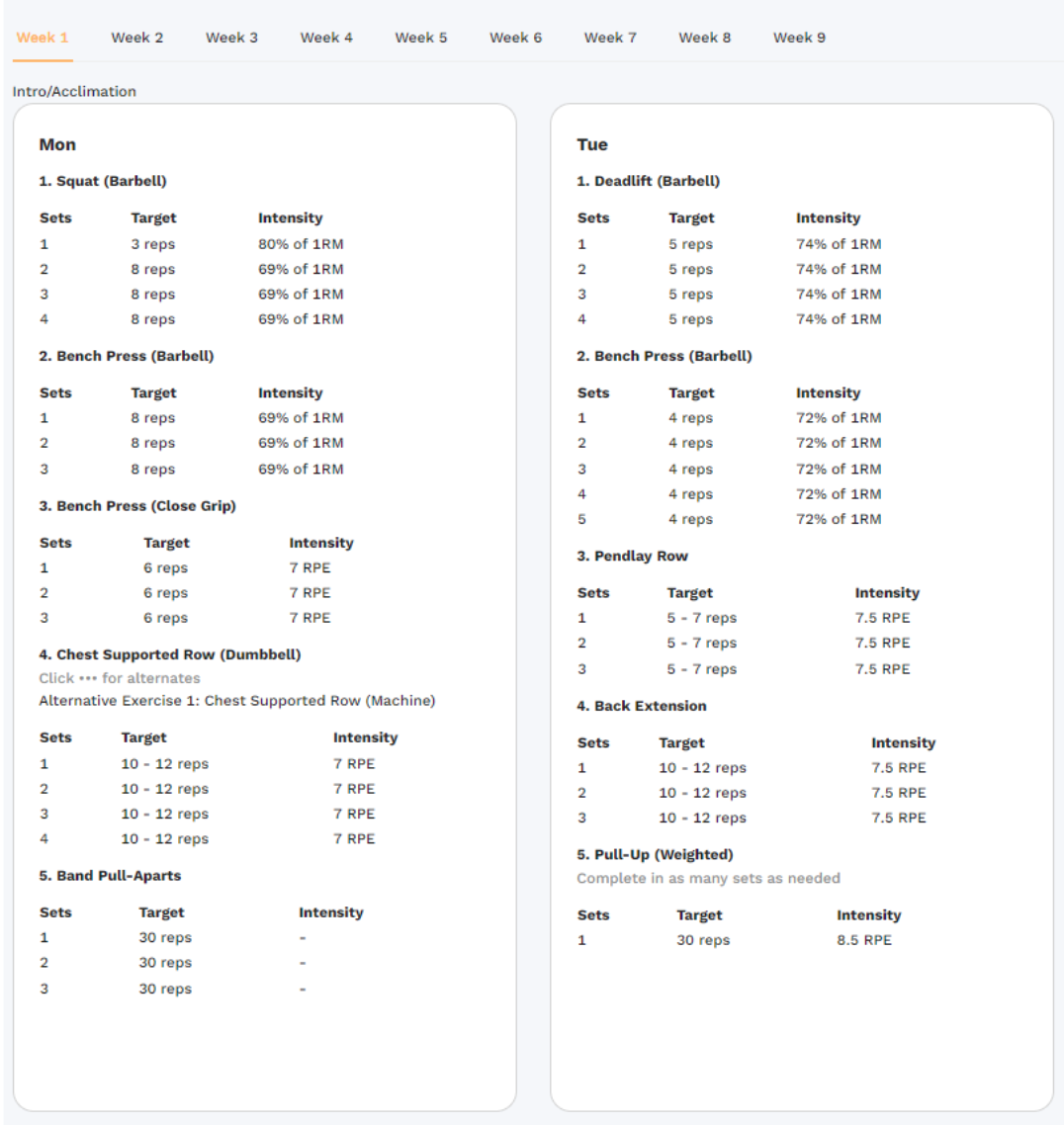

You can get an overview of what training loads are in Boostcamp with the birds eye view on the main page of any program.

Compare this with prior programs you have done to see if you’re making a big jump in intensity or volume when hopping onto a new block. You can also use this information to choose programs that may suit your particular training load better.

Technique

Technique is another culprit that is usually blamed for your powerlifting injuries (1)(4)(5). However this is not as simple as what you might be thinking. The thing is, although technique can play a small role in injuries, everyone’s technique is different so it’s tough to define what a ‘good’ technique is. You can definitely benefit from optimizing your technique to be more efficient and enhance your performance, but the story changes a little bit when you speak about injury specifically. You won’t find data suggesting people who deadlift with ‘x’ technique vs ‘y’ technique will come out ahead on the injury game if load and everything else is equated for. There is a lot more to consider than just technique alone when it comes to injuries.

Your best bet when it comes to technique is to find one that works for you. If you find a particular stance or movement uncomfortable or even painful, feel free to experiment with different variations to find one that suits your body. Also realize that technique is a range. Your technique will change over time and develop as you get stronger. If you’re injured, it’s natural for your technique to change so you’re not in pain all the time. Just be sure not to blame your two mm hip shift, knee valgus, or back rounding for all your issues. There are much bigger things to pay attention to, such as maintaining a neutral position to prevent injury.

External factors

Now lifting itself of course plays a huge role in injuries as discussed, but there is significantly more to the story. Powerlifting injuries are hugely multifactorial, and as such there are many factors in life that can influence your chances of getting injured. Think about your life in totality. Your work stress, personal life, sleep, nutrition, physical activity, social support, and even your income can potentially play a role in why you get injured, especially in severe cases. If you’re going through a stressful time or lacking proper recovery, you can see how the risk of getting injured can be increased. If you try to push big weight with zero sleep and working eighty hour weeks, you simply have less resources to dedicate to your training and as a result, injury can occur.

Miscellaneous

Now sometimes powerlifting injuries just happen. You might have a bar snap on you, or a weight plate drop on you, or you get in a motor vehicle accident and you know, just life. Heck, even a car has crashed into a gym before. Certain things are just outside of your control but the good news is most of these things do resolve on their own with time. However, to avoid these injuries, it is important to start with light weights and gradually increase the weight as your strength improves. Also, use proper form to prevent improper form and don't lift more weight than you can handle.

Lifting belts have also been shown to increase injury in the low back… but hold on a second, you’re probably thinking if you read that right (3). Sometimes when lifters wear a belt, they think they can do a lot more than they can handle and thus increase their risk of back injuries due to using too much weight (refer to the training load section). When overall load is equated for, injury risk is relatively the same. So again be careful what you hear from all the gurus and don’t jump to conclusions because the honest answer is probably more nuanced and uncertain.

What about injury prevention?

You can absolutely reduce the risk of injury when powerlifting. Ensuring you have proper training loads, recovery and efficient technique can help with this as described above. However you can never completely eliminate the possibility of injury when it comes to powerlifting or any other sport. Injuries are unfortunately part of the game, but in most cases all you need to do is find a way to rehabilitate by making training modifications when you get injured.

Roadmap for navigating powerlifting injuries

Alright so now you know what injuries are and some reasons why they might happen to you when powerlifting regardless of how hard you try to prevent them. From here, the key is to learn how to navigate these common gym injuries when they occur and chances are they will at some point. Try not to worry as here is a simple step by step guide on what you can do to overcome this setback and prevent future injuries by practicing proper form.

Step one - assess the injury

Take a breath and assess what happened. You essentially want to perform a needs analysis on yourself to see what your next moves are. Questions to ask yourself include, are you ok? Can you still perform the movement? What hurts? Is there any visible swelling, discoloration or bruising? If there is anything immediately concerning, you should seek out a health care provider for professional help. More often than not, this will not be the case so usually you can relax and continue with your daily activities. You may notice some pain and discomfort after an injury, but you’ll also notice things that you still can do. Take some time to gather yourself and move onto the next steps.

Step two - identify tolerable squat, bench and deadlift movements

Once any serious issues have been ruled out such as a fracture, you can start to see what movements are within your tolerance. Go slow and see if you can still squat, bench and deadlift. You may have to make modifications to the movements for it to be tolerable. Here’s an example of some modifications you can try.

Tempo

Is slowing down or speeding up the lift more tolerable?

Load

Does reducing the weight on the bar help with symptoms?

Sets and reps

Does changing the sets and reps of the exercise help?

Stance and position

How does adopting a wider or narrower stance feel? What about a narrow or wider grip? Or a different bar placement entirely?

Range of motion

If things hurt at the top or the bottom of the range, what if you don’t go to that point? How do partial reps feel?

To further illustrate these training modifications, these are some steps you might take if you injured yourself squatting and are hoping to find a tolerable way to continue squatting.

Try squatting normally, if it hurts then try to slow down the movement with a three second tempo.

If the tempo does not help, what if you reduce the weight? Take off five to ten percent off the weight on the bar and see how that feels.

If symptoms still persist despite reducing load, what about doing less reps or cutting off a set? Reduce reps all the way down to singles and cut a set or two until you find a tolerable range.

If you still can’t manage any sets and reps at any load squatting, then it’s time to see if changing up your squat will help. Try a low bar or a high bar position instead. In addition play around with your stance and see if one feels better than the other. Start with small changes such as moving your grip wider by one finger length and go from there.

If the above still doesn’t work, then see if you can do partial squats. Squatting high or not fully extending the legs might be enough to achieve a tolerable squat movement.

Now sometimes despite doing all this you still can’t find a way to keep squatting, benching or deadlift. That’s ok because the next step will show you that there are many more movements you can explore to build your tolerance back up.

Step three - identify other tolerable movements

If you can’t find any powerlifting movements tolerable, then it may be time to consider other exercises. Just because you can’t squat, bench and deadlift does not mean you cannot make gains in the gym. It’s easy to have tunnel vision as a powerlifter when your life and sport circles around three main lifts. However when you zoom out, you’ll soon realize that there are a plethora of other exercises that you can incorporate in your training to further your progress even while injured.

Think about the individual lifts and what you want to achieve with them. This will help you find a suitable replacement that is as close to the original exercise as possible. Here’s a brief overview of what you might want to try when considering a replacement exercise.

Try a similar exercise using different equipment

If you can’t find a way to back squat, what about a front squat? What about a leg press? There is usually a movement that is similar to the original exercise that you might be able to tolerate.

Try exercises that isolate muscle groups

In the squat you are mainly training your legs. So if you can’t squat you can at least find exercises that target the muscles used in that movement. Whether it’s free weights or machines, you are bound to find something that can work with your specific injury such as a knee extension or leg extension machine.

Look beyond the injured area

Sometimes you might just have to take some time off and that’s ok. You can still train and build other areas of your body. If you can’t train your lower body then focus on the upper body for now. If you can’t train one leg, you should still train the other one. This can actually help maintain and improve performance in other limbs by a process known as ‘cross education’ (6). Besides, you’ll feel alot better both physically and mentally if you continue to stay active in the gym.

Try a different sport

This is temporary, but sometimes disconnecting from the sport you injured yourself in can be therapeutic. Pursuing something else in the short term provided you have the time and interest can help you recover. More importantly, it keeps you active and focused on the things you can do when experiencing pain. Athletes that identify with more than just their sport usually come out ahead as they are more resilient when dealing with setbacks.

Rehab is just modified training. With these steps you can always find something you can do whatever your injury may be. It can be frustrating, but take some time with it and focus on the things you can control.

Pro tip: you can apply the same concepts in step two with any other exercises you choose to do, not just the three main powerlifting movements.

Step four - plan your rehab program

You should now have an idea of what you can and cannot do temporarily at the gym. Keep in mind this will change overtime as your injury takes its typical recovery course. You can use this information to guide your powerlifting training during this time.

If you go back to our squat example, let’s say you found tempo goblet squats at low loads tolerable and also found machine exercises such as a leg extension and leg curl to feel good. You can use the goblet squats to replace your back squat training in the meantime and incorporate those accessories in your training to make up for the lack of overall tonnage from the absence of back squats. Eventually, you will want to try back squatting again when it’s tolerable, so you can add in a day where you try to squat just the bar and use that to gauge your progress. As you progress through your rehab program and recover from your injury, you’ll slowly reintroduce more back squatting and less of the goblet squats and accessories.

There is always something you can do. If you can’t think of anything, feel free to browse the various Boostcamp programs available and sample a few workouts to see if they are tolerable. If you do find a workout you want to perform, consider using some of the strategies mentioned in steps two and three to make the exercises more tolerable when working around injuries.

Programming Strategies for the Injured Powerlifter

You now have an approach to deal with any injury that may occur. Of course every situation is different, but having a framework can help you deal with and bounce back from potential setbacks. Here are some programming strategies and ideas you can incorporate in your rehab program to guide your journey back to the platform.

Minimal effective dose - Low load and volume

When things hurt, you might be wondering what the minimum amount of training you can get away with and still make gains is. The good news is there is research that tells us what this is. This form of training is known as the Minimal Effective Training Dose or METD for short. Powerlifting athletes looking to train with a METD approach can do so by performing 3 to 6 total working sets per week, with repetitions ranging from 1 to 5. These sets can be spread out over 1 to 3 sessions using loads above 80% of your one rep max, with a Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) of 7.5-9.5. You can expect to gain strength using these parameters in programs lasting about 6 to 12 weeks (7).

Most Boostcamp programs will meet the METD threshold, so you can use this as a guide when looking to reduce training volume with any program. If you’re struggling to perform your typical training workload due to pain or injuries, you can rest easy knowing gains are still possible with a reduced dose of training.

Making accessories your primary lift

In the short term it’s perfectly ok to make an accessory your primary lift. If bulgarian split squats feel great for you (you’re probably lying), then make that your focus for the next block. This will allow you to push your body and facilitate adaptations while your body recovers from injury. Of course your focus is still on the big three lifts, but you may benefit greater from pushing a movement that is tolerable. This time away from squatting, benching, and deadlifting can be the refreshing break you need to ultimately put more kilos on the bar when it counts.

Programming over a longer timeframe

When it comes to powerlifting injuries, most are self limiting issues that resolve themselves with time. So if you think about it, injuries are only really an issue when bound by a definitive amount of time. Zooming out and programming over a longer period of time can help with this. Try planning your microcycles over two weeks instead of one. Try having a block that is months in length versus weeks. Giving yourself more time to progress and heal in your programming blocks can help you adjust your expectations and give you more flexibility when returning to training. After all time is a construct, so who's to say a week can’t be made up of 9.5 days?

Have a Plan A, B and C

In your programming, plan to have different lifts that you can perform in case things flare up or feel bad on the day. If you plan to bench but it's not quite tolerable, have a back up plan such as a 2 board bench or a dumbbell chest press. On the flip side if you planned pushups but your pec feels good then have the flexibility to try some bench pressing. Progress is not linear, you will find days where you feel better and days where you feel like absolute trash. Integrating backup plans into your program will help you stay on track and keep active even when things hurt.

Supplementary Care for the Injured Powerlifter

If you’re reading this article, you’re probably battling an injury and stumbled upon this while searching for help. If you spent any time browsing social media along the way, you will have likely come across content promising a quick fix here and there. Whether it’s cryotherapy, getting adjusted, cupping therapy, or some stimulating needles, you are probably curious if this is something you need to do for your injury.

In general, you can think of all these things as potential symptom modifiers. They can potentially help you feel better in the short term but they are not a fix. Your best plan of attack when dealing with injuries is still coming up with a plan to continue training by pushing movements that are tolerable under specific circumstances. Eventually you will return to normal training, so don’t chase after different modalities in hopes of finding a cure for your current injury or for preventing future ones. If you do opt for alternative care, consider choosing something that you enjoy and is cost effective for your own particular situation. If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. If injuries were that simple, then no one would be injured! Don’t sweat the small stuff and focus on the heavy hitters. Trust the process and you will inevitably find yourself back on the competition platform, with less inflammation and a faster recovery time.

Lifting Programs

When it comes to finding a good lifting program, the Boostcamp App is the place to look. No matter your goals, whether it is bodybuilding or a strength sport or something else, you can find a program on Boostcamp. However, if you don't like the pre-written programs, you can create your own! You can also track your progress throughout each program.

Powerlifting Injuries Wrap Up

Setbacks and injuries are part of the game, but it doesn’t have to be the end of your story. If you’re an injured powerlifter, there are many ways to navigate your training while natural history takes care of the rest. Regardless of what you are dealing with, the key is to find an entry point and a qualified professional is always available to help you find your path forward.

If you find yourself injured, don’t lose hope and try to focus on the things you can control. Give it enough time, and you’ll eventually come out stronger and inevitably add some kilos onto your total. They say what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, and in this case you will come out a stronger and more resilient powerlifter.

Check out the Boostcamp App for some great programs. Also, be sure to follow Boostcamp on Instagram and subscribe on YouTube!

References

Strömbäck E, Aasa U, Gilenstam K, Berglund L. Prevalence and Consequences of Injuries in Powerlifting: A Cross-sectional Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 May 14;6(5):2325967118771016. doi: 10.1177/2325967118771016. PMID: 29785405; PMCID: PMC5954586.

Aasa U, Svartholm I, Andersson F, Berglund L. Injuries among weightlifters and powerlifters: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Feb;51(4):211-219. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096037. Epub 2016 Oct 4. PMID: 27707741.

Siewe J, Rudat J, Röllinghoff M, Schlegel UJ, Eysel P, Michael JW. Injuries and overuse syndromes in powerlifting. Int J Sports Med. 2011 Sep;32(9):703-11. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1277207. Epub 2011 May 17. PMID: 21590644.

Bengtsson V, Berglund L, Aasa U. Narrative review of injuries in powerlifting with special reference to their association to the squat, bench press and deadlift. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018 Jul 17;4(1):e000382. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000382. PMID: 30057777; PMCID: PMC6059276.

Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Resistance training among young athletes: safety, efficacy and injury prevention effects. Br J Sports Med. 2010 Jan;44(1):56-63. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.068098. Epub 2009 Nov 27. PMID: 19945973; PMCID: PMC3483033.

Green LA, Gabriel DA. The cross education of strength and skill following unilateral strength training in the upper and lower limbs. J Neurophysiol. 2018 Aug 1;120(2):468-479. doi: 10.1152/jn.00116.2018. Epub 2018 Apr 18. PMID: 29668382; PMCID: PMC6139459.

Androulakis-Korakakis P, Michalopoulos N, Fisher JP, Keogh J, Loenneke JP, Helms E, Wolf M, Nuckols G, Steele J. The Minimum Effective Training Dose Required for 1RM Strength in Powerlifters. Front Sports Act Living. 2021 Aug 30;3:713655. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.713655. PMID: 34527944; PMCID: PMC8435792.